Scars

Two of the many things I love are dogs and running. One February morning, early enough to bite at my cheeks and nose, but late enough that the sky was just beginning to blush, I was out for my morning run. It was a Saturday, so traffic was quiet, and the morning mist was hovering over lawns wet from the night’s dew.

When I’m running, I can get really lost in my thoughts and lose all awareness of my surroundings, so I didn’t notice the three dogs come out from the open gate until they were in the air, jaws open, just inches from my face. I managed to get my arm up in time to protect my face, but two of them sunk their teeth deep into the flesh of my arm, one just above my elbow and one just below. The third couldn’t get around the first two to reach me. They were pit bulls, I came to realize as they shook my arm and the third tried again to leap over the two that had me in their jaws. My only thought was, “I can’t kick them or they could knock me down.” To be honest, I’m not sure how long they shook my arm before I looked back and they were all three running, ears back and tails down, back to the open gate they came from. It didn’t take long for me to think, if you’re running away, so am I, and I ran about 10 yards before I started to feel dizzy and nocuous and noticed the blood seeping through my shirt and running out of my sleeve. I stopped and sat down with my head between my knees so I wouldn’t pass out. A car stopped beside me and a woman who was passing by in the opposite direction who saw the attack, called 911, and came back to help me had her arm around my shaking shoulders. After she got me in the warm passenger seat of her car, she asked me, “how did you get them to let go and leave you alone? They had you.”

I looked up and said, “I don’t know. I think an angel must have showed up.”

She got a very concerned look on her face, patted my shoulder, and said, “I think you’re just upset.” She waited several feet away from me until the police and aid car arrived.

For days, I couldn’t run outside. For weeks, I had nightmares of dogs coming at me and I’d wake up terrified. So, I started memorizing the book of Colossians as I went to sleep and filled my mind with something other than the memory of that terrifying experience. My husband ran with me when I first ventured to run outside again. And, slowly, my fear healed and faded to match the faint scars of their teeth marks on my arm that my kids assure me are cool. Now, years later, frequently when I wear short sleeves, someone will ask me, “what bit you?”

There was a 9.2 earthquake off the coast of Alaska in 1964. The damage to Anchorage and the surrounding cities was devastating. The tsunami that followed is the largest ever recorded reaching 1,720 feet (taller than the Empire State Building) when it struck the tall banks of Lituya Bay. While the cities are fully rebuilt, 80 years later, you can see the scars left on the landscape from the tsunami.

My grandparents grew up during the depression. They always, always, always cleaned their plates. And when you were at their house, so did you. Food was precious to them. My grandpa made logs for the fire out of newspapers wrapped in wire and fished the wire out of the fire and re-used them until they were so brittle, they broke. My grandma canned hundreds of jars of beans, peaches, pears, apple jelly, jam, pickles, beets, onions, carrots, and everything else that grew in their garden every year. She could tell you with pin-point accuracy how many jars of each she had at any given time and from what year they came. You couldn’t see those scars, but they never left them. My sister, brother and I used to spend weeks at a time at their house each summer helping pick the fruits and vegetables and can them. We loved the rows and rows of jars filled with green beans and apple pie filling on shelves in our garage all year long. We understood why we always had to clean our plates at Grandma and Grandpa Rhodes’ house. We didn’t necessarily see them as scars, but they were cool to us. Maybe not the homemade clothes, but the rest, that was cool.

My brother’s ears are ridiculous. He has been wrestling since he was 10 years old. I’m not even sure what the medical term is, but wrestlers call it cauliflower ear. After years of grinding your ear against the mat, day after day, they become so disfigured, they don’t even look like ears. He cannot use headphones unless they’re the huge over the whole ear kind, and even those don’t really fit quite right. Forget about a Q-tip. It’s caused by fluid filling the entire ear, every fold and canal after the insult of being ground against the mat. The headgear doesn’t help prevent this. Over time, this fluid hardens to feel just like cartilage, kind of like the bridge of your nose. In fact, his are so notorious, they earned him a spot in a pre-Olympics Nike commercial once upon a time that featured many Olympians and their scars, battle wounds, earned from years in their respective sports. Now that he’s retired from both wrestling and ultimate fighting, he could have them repaired and restored to look like ears again, but he wouldn’t dream of it. He loves them for he’s earned them, and they are his battle wounds, hard earned and hard fought.

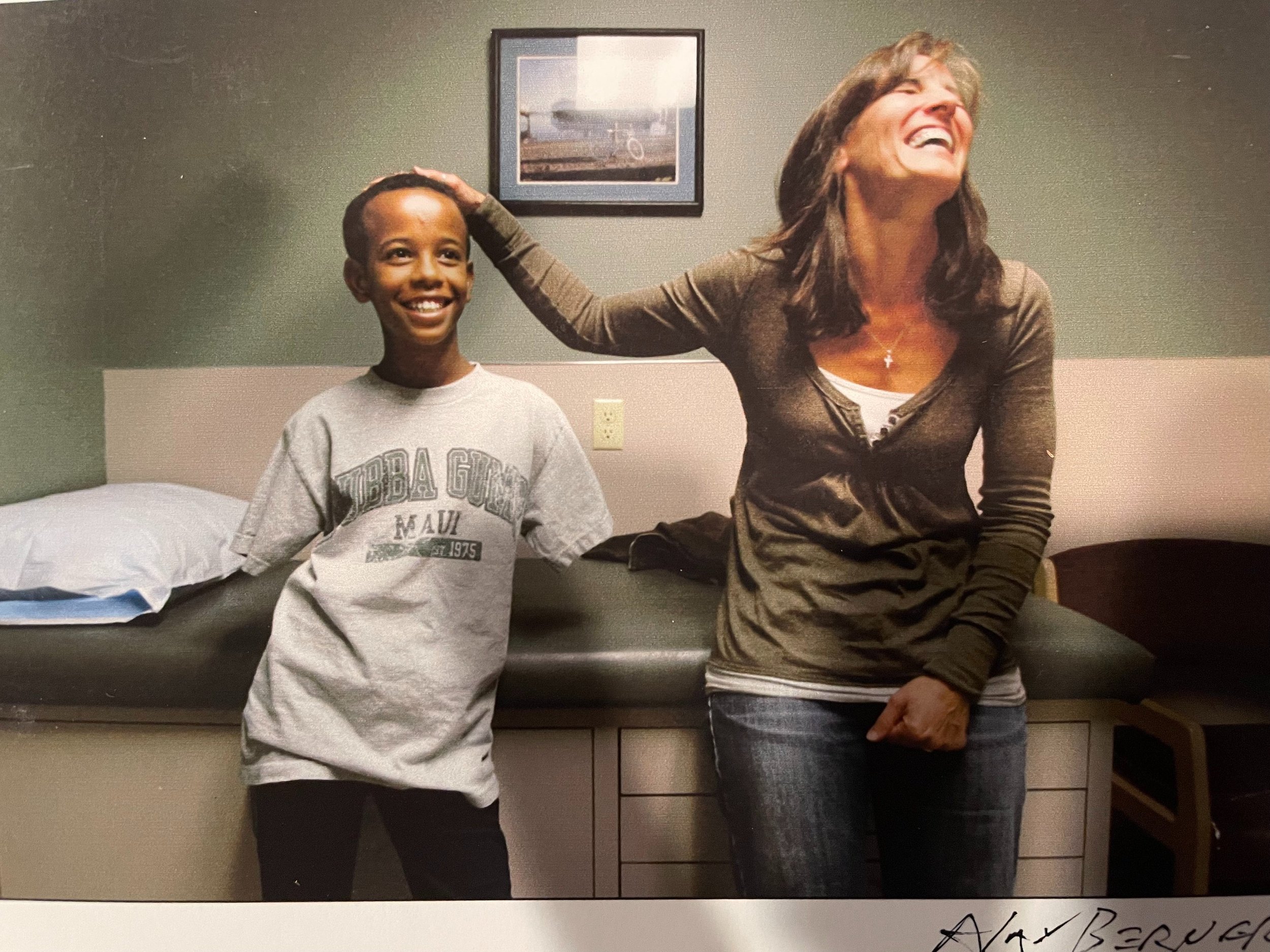

There was a time when a young boy from Ethiopia lived with our family for a few months. He came to the US for medical treatment. He’d lost both of his arms in an act of unspeakable violence. One arm was too damaged for a prosthetic limb, the other barely long enough. But oh, how he loved to swim. While it was not me walking from the locker room to the crowded pool deck with bare stubs for arms while children and parents alike stared after him, I felt his discomfort. There was no language barrier for this pain. My family and I helped him eat, brush his teeth, dress, bathe, scratch the back of his head, and buckle his seat belt, to name a few things he needed help with. These are independences toddlers fight for and demand from their parents. He was 14. It was a terrific battle between helping him and helping him learn to do these things for himself, especially after he got his “arm.” It was a triumph to watch him ride his custom-made bike. It was a triumph and a heartbreak to see him go back home to Ethiopia with one prosthetic arm and as many supplies to support its use as possible. Can these scars ever be cool? Perhaps language is failing here. Cool. Emblems of resilience. Signposts of pain. Heralds of healing. Storytellers. Historians.

As the COVID-19 pandemic transitions to an endemic, the speculation of what the scars will be are emerging and taking shape. On the young children whose first social interactions with the public have been distanced and through masks, on school-aged children whose first school experiences have been disrupted and online, on middle-aged children who didn’t develop social skills with their peers, on middle and high school aged children who didn’t go through the process of connecting more with adults outside their families and with their peers than with their parents and siblings – if they were fortunate enough to have them, on adults who were confined to their homes and small or non-existent social circles for such an extended period of time, on society as a whole after witnessing so much death and protracted uncertainty, on the nurses and doctors who cared for the dying day by day and month by month as not only medical providers but surrogate family members for last breaths, on the local and global economy, on international relationships, the list could go on and on. What will the scars look like and how will the wounds heal to be scars? How will today’s children describe their grandparents who grew up during the pandemic like I’ve described my grandparents who grew up during the depression?

Will these scars be cool? A scar can be a sign of pain and trauma or an emblem of resilience and healing. Too often all we see are the scars or end result, and don’t understand what happened between the injury and the resulting scar. Dr. Brene Brown in Rising Strong calls this gold-plated grit where we gloss over the messy second act and skip right to the end where the moral, gem, lesson lies. No one wants to talk about the nights after the dog attack I bolted up out of sleep terrified from a nightmare of dogs coming at me. No one wants to hear about the mornings I stood paralyzed by my front door with my running shoes on unable to step outside. No one wants to talk about the time my husband got a little too far ahead of me on those first mornings running back outside and I panicked and stopped, unable to even take a step. Or about the time, months later when I was walking with my daughters and a huge dog inside a car barked and lunged at the windows at us. Before I knew what was happening, I was flat on my face on the ground shaking. It took both of them to get me back up and away from the barking dog. Mine was a terrifying, but quick experience. My scars are visible but coverable and manageable. I don’t mean to minimize what a life-threatening or excruciatingly painful experience may have been like, one that may have left life altering scars – visible or not. Scars can be cool, if they heal to an emblem of resilience. But don’t gold plate that process. It’s not easy. And not all scars are easy to bear. But what I’ve learned from those with scars from trauma far worse than any of mine, they can heal.